Some fires can never be put out

It's not only Pearl Harbor Day but the anniversary of the worst hotel fire in U.S. history

Oak City Cemetery is on the north edge of Bainbridge, not far from the banks of the Flint River. Like most old cemeteries, it is both a final resting place and a history book. There are stories between the lines of the epitaphs carved into tombstones and grave markers.

Marvin Griffin, the first man in Georgia to hold the offices of adjutant general, lieutenant governor and governor, is buried at Oak City. So is Miriam Hopkins, a hometown girl who was an Academy Award-nominated actress with two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. (She auditioned for the role of Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone With the Wind” – the only candidate who was a native Georgian – but the part went to Vivian Leigh.)

The grave of my maternal grandfather is at Oak City. His name was Charlie Curtis Smith. He died of pneumonia at age 27 after going on a fishing trip. My grandmother was pregnant with my mother, who was named after the father she never knew.

Years ago, I took my mother to visit her father’s grave when she pointed out, with great sorrow, the headstones of seven Bainbridge High School students killed in the famous Winecoff Hotel fire.

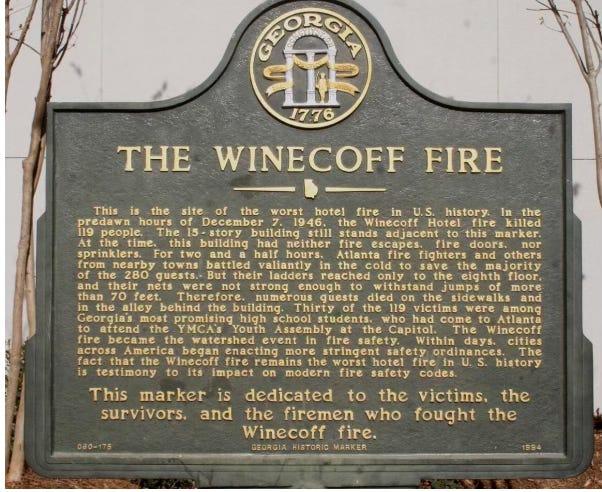

They were among the 316 teenagers attending the annual Georgia YMCA Youth Assembly at the state capitol in Atlanta on December 7, 1946. It was exactly five years to the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Thirty of those young people died in the worst hotel disaster in U.S. history, which killed 119 people. (For 25 years, the Winecoff was the single deadliest hotel fire in the world. It lost that distinction on Christmas Day in 1971 when 164 people were killed in a gas explosion at the Daeyeonggak Hotel in Seoul, South Korea.)

You can imagine the collective heartache of a small South Georgia town, where everybody knew everybody. Five promising young women and two popular young men – both Boys Scouts – died of smoke inhalation or jumped to their deaths in desperation from the ninth floor of the 15-story hotel. Among them was Patsy Griffin, who was Marvin Griffin’s 14-year-old daughter.

The tragedy hit home for my mother and never left. She was born in Bainbridge, and she graduated from high school in Fitzgerald, where she knew four members of a family who died in the fire. As a teenager during World War II, she once went on a shopping trip to Atlanta and stayed at the Winecoff. A few years later, when she was a sophomore at North Georgia College, she answered the telephone in the hall of her dormitory. It was a call for a young lady in the dorm, who was told her mother had been killed in the fire.

A decade later, I was born at Atlanta’s Georgia Baptist Hospital, less than a mile from the hotel. Over the years, the Winecoff has become personal for me on many other levels. In 1993, a former newspaper colleague, Sam Heys, co-wrote a book called “The Winecoff Fire: The Untold Story of America’s Deadliest Hotel Fire.’’ And, in December 2007, I interviewed Ed Kiker Williams, of Cordele. He was a 17-year-old boy on a trip to Atlanta with his family. His mother, 8-year-old sister, his aunt and three cousins all died in the blaze.

More than 2,300 people lost their lives in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a day that marked America's entry into World War II. It was a war that killed more people, destroyed more property and changed the world more than any military conflict in history. In the shadows of that somber anniversary is the tragedy that happened five years later. The Winecoff billed itself as "fireproof" in the same way the Titanic was supposed to be "unsinkable." But 280 guests filled the 194 rooms that night, and almost half of them did not live to see the sunrise the next morning.

It broke the heart of a state and nation. They came from towns like Gordon, Barnesville, Claxton, Cornelia, Douglas and Cedartown. They were fathers, mothers, teachers, secretaries, traveling salesmen, bus drivers and servicemen who had returned home from the war. They were grandparents. They were children. Church cemeteries and family graveyards are the placeholders for those left behind, who cannot and will not forget.